Iambic pentameter is a two-syllable five-foot poetic meter with stressed even syllables. It can be called the most classic of the poetic meters in English as Shakespeare used it in his plays. Poems and songs written in iambic pentameter are known to every person because renowned poets and bards have actively used this poetic foot since time immemorial.

Conventional poetry is what everyone thinks of when they have to come up with examples of iambic pentameter. However, nothing prevents us from thinking outside the box. While most English song lyrics use irregular poetic meters for catchy and unique sound effects, some rely on traditional feet, so by including those songs into our list of examples we can both show the varieties of iambic experience and have some fun in the meantime.

The Origins and History of the Iambic Meter

The iambic foot officially dates back to the ancient Greek poet Archilochus (c. 689–640 BC), yet he was not the inventor of the meter. Iamb’s roots are found in ritual folklore and cult songs of the ancient Greeks who glorified Demeter, the patroness of agriculture. According to the myth, searching for her kidnapped daughter Persephone, the goddess left Olympus and settled in the palace of the Eleusinian king Keleus under the disguise of an old mortal woman. Once she learned about Persephone’s death, the only one who could brighten up the goddess’s mood with her raunchy jokes was the female servant Iambe whose name evolved into the name of the meter.

In the cult of Demeter, it was customary to drench the participants of folk festivals in rude ridicule and sarcastic jokes. They were often obscene and cynical, as Iambe’s standards demanded. In his “Poetics“, Aristotle himself notes how the iambic foot is similar to the rhythm of colloquial speech (which is the reason why the iambus remains the most popular poetic meter).

The term ” iambic ” – “ἴαμβος” – goes back to the musical instrument “ἰαμβύκη”, to the accompaniment of which iambics were originally performed. In folklore, the word “ἴαμβος” was associated with the comic nature of the poems composed in it.

What is Iambic Pentameter? The King of English Poetry

The history of poetry proves that iambic pentameter is in tune with the natural rhythm of the English language. The iamb is able to convey the polyphony of feelings, both the dialogue and the monologue, a lonely voice and the crowd’s roar alike. Also, iambic pentameter is equally suitable for small lyrical forms (elegy, ode), and narrative poems.

Iambic pentameter is the standard meter in sonnets; unsurprisingly, William Shakespeare is the author of the most famous example of iambic pentameter in English poetry.

How the Iambic Pentameter Works

As you know, the iambus is a two-syllable meter. Its foot (a rhythmic group of a particular duration) consists of two syllables: one unstressed, the other stressed, in this order. Schematically, the iambic pentameter can be represented as

UÚ | UÚ | UÚ | UÚ | UÚ

For example:

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme…“Ode on a Grecian Urn” By John Keats

The second (stressed) syllable creates the feeling of pressure and downward movement while the first (unstressed) syllable is lighter, moving upward. This undulation resembles the rhythm of calm breathing which is natural for a person and therefore easily perceived.

Wondering how to write in iambic pentameter? Learn how to write poetry!

Iambic Pentameter Examples…

Not that we know what iambic pentameter is and where it came from, let’s consider some examples of this meter in songs.

Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Mississippi Kid” alternates iambic pentameter in the odd lines while most of the even ones leverage iambic trimeter:

Another example of iambic pentameter in songs is found in the opening lines of each stanza in “The Earth Will Shake” Thrice:

Each stanza and chorus in Pink Floyd’s “Brain Damage” uses the iambic pentameter intermittently with iambic tetrameter and iambic hexameter:

Were you able to find all the iambic pentameter lines? One of them is:

I’ll see you on the dark side of the Moon

… & Errors

At this point, you may be wondering: why spend so much time explaining the iambic pentameter when it is so simple and straightforward? Well, as it turns out, some people who claim to understand the meter have no idea what they are talking about. Instead of going through all the mistakes in that read, let’s focus the crown of its fallacy: Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off” which the article puts on top of the iambic pentameter examples in song lyrics.

Here are the lines of that song (minus repetitions) — with callouts of what meter is actually used in each:

I stay out too late — trochaic dimeter

Got nothing in my brain — iambic trimeter

That’s what people say, mm, mm — trochaic dimeter

That’s what people say, mm, mmI go on too many dates — trochaic trimeter

But I can’t make ’em stay — iambic trimeter

At least that’s what people say, mm, mm — iambic trimeter

That’s what people say, mm, mm — trochaic dimeterBut I keep cruising — iambic dimeter

Can’t stop, won’t stop grooving — trochaic trimeter

It’s like I got this music in my mind — iambic pentameter

Saying it’s gonna be alright — anapaestic monometer + trochaic dimiter

‘Cause the players gonna play, play, play, play, play — trochaic pentameter

And the haters gonna hate, hate, hate, hate, hate — trochaic pentameter

Baby, I’m just gonna shake, shake, shake, shake, shake — trochaic pentameter

I shake it off, I shake it off (Whoo-hoo-hoo) — iambic tetrameterHeartbreakers gonna break, break, break, break, break — iambic pentameter

And the fakers gonna fake, fake, fake, fake, fake — trochaic pentameter

Baby, I’m just gonna shake, shake, shake, shake, shake — trochaic pentameter

I shake it off, I shake it off (Whoo-hoo-hoo) — iambic tetrameterI never miss a beat — iambic trimeter

I’m lightning on my feet — iambic trimeter

And that’s what they don’t see, mm, mm — iambic trimeter

That’s what they don’t see, mm, mm — trochaic dimeterI’m dancing on my own (Dancing on my own) — iambic trimeter

I make the moves up as I go (Moves up as I go) — iambic tetrameter

And that’s what they don’t know, mm, mm — iambic trimeter

That’s what they don’t know, mm, mm — trochaic dimeter…

Hey, hey, hey,

Just think while you’ve been gettin’ down and out about the liars

And the dirty, dirty cheats of the world

You could’ve been gettin’ down — recitative (no meter)

To this sick beat — iambic dimeterMy ex man brought his new girlfriend — iambic trimeter

She’s like, “Oh my God!” — amphibrachic dimeter

I’m just gonna shake — trochaic trimeter

And to the fella over there — iambic tetrameter

With the hella good hair — trochaic trimeter

Won’t you come on over baby? — trochaic tetrameter

We can shake, shake, shake (Yeah) — trochaic trimeter

Yeah, oh — trochaic monometer…

So, there are two iambic pentameter lines in this entire (very irregularly metered) song, one of which gets there only by repeating the same word (“break”) five times.

Ridiculous as this example is to anybody who passed high school English, this is what happens when copywriters write about things they are clueless about. Hopefully, our article will save you from such embarrassment. And, to consolidate the knowledge and make sure you are ready to call any iambic foot by its real name, let’s consider the other types of iambus.

The Varieties of Iambic Experience

While iambic pentameter is undoubtedly the most popular meter in classic English poetry, iambus comes in other sizes, too. Depending on the number of feet used in a line, iambic verses can be divided into the following types.

Iambic Monometer

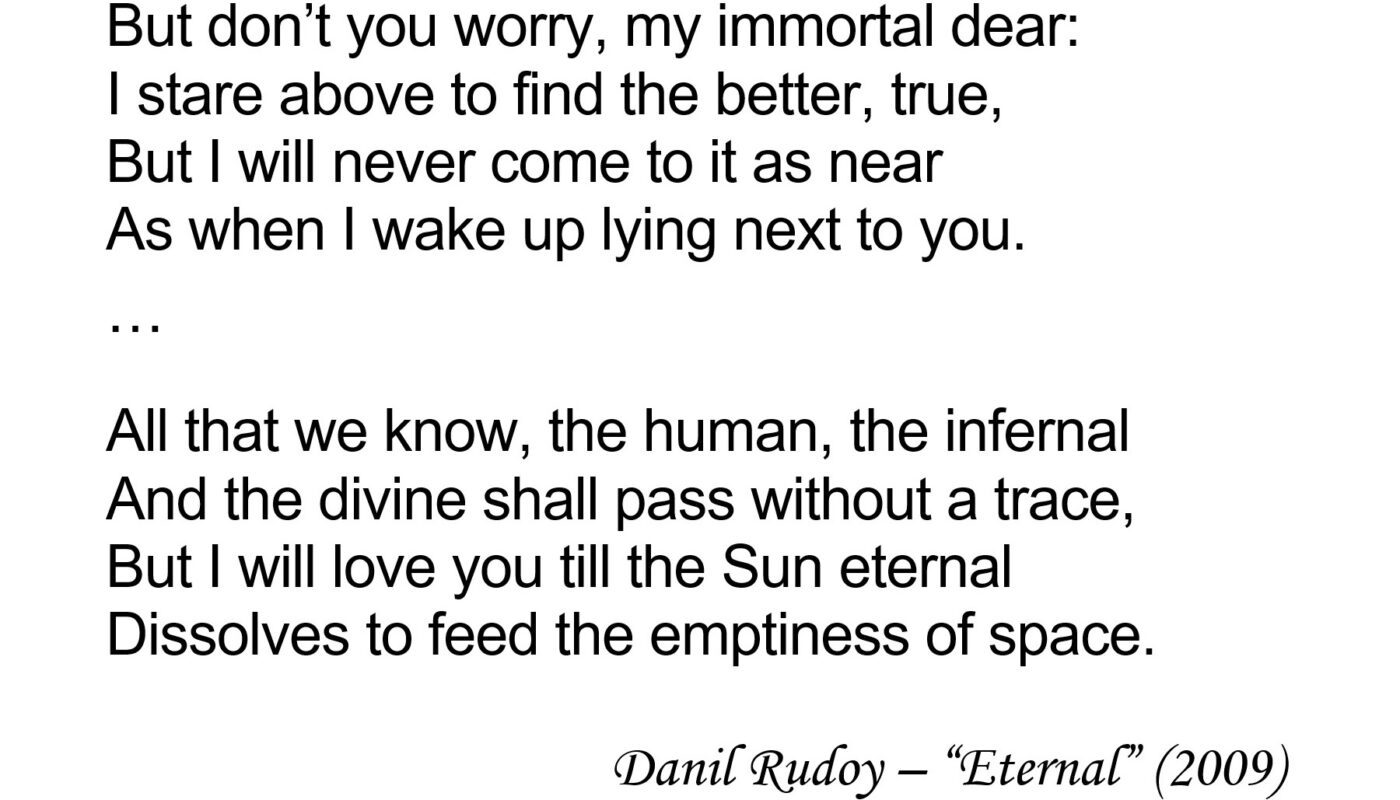

Iambic monometer is one of the two hardest poetic meters that exist (the other one is the trochaic monometer). Due to its staggering complexity, (the shorter the lines, the harder it is to rhyme them meaningfully) poems entirely composed in iambic monometer are so extremely rare that most poets (including best ones) haven’t produced a single fully-fledged one. “Friday Night” by Danil Rudoy is an exception:

Dim light,

Ash-tray.

To-night

We play.

The stake

Is high:

You fake,

You die!

The poet manages to continue the coherent narrative for three more stanzas, eventually arriving at a logical denouement. You can find the full version of “Friday Night” in Rudoy’s new collection “Love is Poetry”.

Iambic Dimeter

Iambic dimeter is also hard, but not as insanely as its monometer relative. While the single-footed iambus resembles a series of shots fired into the bull’s eye, the two-foot iambic meter is marked by easily perceptible (almost palpable) lightness and grace. Iambic dimeter creates the impression of not just accelerated but intermittent breathing:

Get even flatter,

Erase the score:

It does not matter

To me no more.

You’ve crossed the tropic

That lies above

My misanthropic

Approach to love.

D. Rudoy — “My Misanthropic”

Note the unstressed syllables at the end of “flatter”, “matter”, etc.: they are akin to short pauses that give the iambic dimeter the rhythm and the cadence of a noble waltz.

To capture the flow difference between the iambic monometer and dimeter (also reflected in the longer iambic feet) consider another poem by Rudoy where he casually switches between the two meters, either showing off or just having a great time:

Insomnia

Evaporates.

The night

Is at risk.

How phony: a

Charade of dates

That might

Have been brisk,

Begins to flaunt

A marriage coo.

I squeeze it

And end:

I bet you won’t

Have courage to

Come visit

Your friend.

D. Rudoy — “Insomnia”

Iambic Trimeter

Iambic trimeter is also relatively short and easy to listen to. Its fast pace fits best with humorous or satirical lines; however, most of The Animals‘ “House of the Rising Sun” is written in iambic trimeter:

Note that the opening line (“There is a house in New Orleans“), as well as the third lines of each stanza, represent not the trimeter but the iambic tetrameter.

Iambic Tetrameter

Iambic tetrameter is medium in length, varied, and very rich rhythmically. It is a considerably more popular poetic meter than its shorter counterparts not just in English poetry but in European languages in general.

Iambic tetrameter brings out the shades of tragedy and comedy alike: a monumental epic and a sentimental romance can be composed in it with equal ease. The iambic tetrameter also provides an excellent framework for a philosophical reflection in an elegy, such as ELP’s “Lend Your Love To Me Tonight”:

It is a perfect example of iambic tetrameter — except for the opening line, which is missing the first unstressed syllable, thus turning into a trochaic trimeter.

MUSE habitually leverages iambic tetrameter. For example, the hit song Supermassive Black Hole is written mainly in this meter (except for the refrain featuring free verse and ending in iambic trimeter):

And, just in case you thought the iambic tetrameter was all elegiac, philosophical, and romantic, it makes most of Johnny Cash’s “A Boy Named Sue” where only the third and the sixth line of each stanza switch to iambic pentameter:

Iambic Hexameter

The last of the commonly used iambic feet is the iambic hexameter. It is a long meter that usually includes the caesura (a pause in the middle of the line that seems to divide iambic hexameter into two trimeter but doesn’t, unless there is a rhyme to go with the caesura). The inherent slowness is the reason for the limited rhythmic variety of the iambic hexameter which is characterized by a feeling of ductility, unhurried breathing, deep thought, and profound lyricism.

Naturally, rules are meant to be broken, and who would we expect to break them if not The King himself? So, let’s rock, and let us know in the comments how you feel about this article compared to all the other iambic ones out there.